“There are five virtues; if they do not exist in writing, it is a hopeless business to be a master in writing by reason only: Precision, inquiry in writing, goodness of the hand, patience in labor and perfection of writing tools. If you lack one of these five virtues there will be no use, even if you try for a hundred of years.”

–Unknown calligrapher

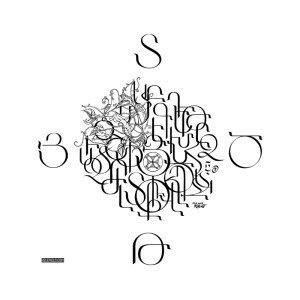

Calligraphy (Greek: kalligraphía, neat handwriting; from κάλλος, beauty, and γραφή, writing): the art of beautiful and legible handwriting born to encode and decode speech in a visual form.

Two years ago, I received a request from the editor of the “Encyclopedia of World Calligraphy” to contribute to an upcoming edition by drawing samples of Armenian script. I was told that they needed all four major scripts executed with sequence of strokes (the direction of writing). For over three months, I spent my nights drawing letters, digging out anything I could find on my bookshelf, only to discover that calligraphy as a discipline was a rare find in the rich legacy of Armenian culture. How could it be, I asked myself, that we have so little written about it? We have studies of paleography (the science of writing) but practically nothing on calligraphy (the art of writing).

Why didn’t calligraphy as an art form evolve in the Armenian cultural tradition? Was it because, at the time of the creation of our alphabet, the art of writing had a very practical purpose? Why did it stay confined to the boundaries of manuscript art for centuries? A dominant part of Western medieval culture and a lifestyle in the Far East (the Japanese take calligraphy as a compulsory subject in schools), calligraphy in the Armenian tradition is certainly one of the least explored and studied areas. What was different about us?

The material I had access to only scratched the surface. But one source of information was close by and accessible: the Gulbenkian Library in the Armenian Quarter of Jerusalem’s Old City. Thousands of printed books in the library and some incredibly beautiful manuscripts are sadly locked up there in the Etchmiadzin chapel. I had never seen them, and the chance I would be allowed anywhere near it was dim. Yes, it is a very complicated reality and we are not champions when it comes to sharing our own legacy, even among each other. So I turned my eyes to the Matenadaran in Armenia. Interestingly, what I was looking for was not in the Matenadaran but in the Literature and Art Museum. I found out that we did have calligraphy as a subject as part of our classical education before the genocide, and that a few precious schoolbooks had survived. They were published in Nor Nakhijevan (1870), in Venice (1834), and in Tiflis (1884).

***

Beautiful writing is art. There is no doubt in my mind about that. And perhaps the reason why we have difficulty with contemporary Armenian lettersets is because we have not built our practice today on what we had known and forgotten.

I was deeply convinced that our letters were meant for more than just communicating written words. Their complexity and simplicity is puzzling. Their origins are obscure; despite a largely accepted consensus over the origin of most of the letters, interesting discoveries are still being made and everything can change overnight. The discovery of the Armeno-Greek papyrus is a prime example of that. It’s the oldest surviving example of Armenian handwriting. No other papyrus with Armenian characters is known. Dated around the 6th century, it’s written in Greek using Armenian letters. But what letters? It’s clearly not Mesropean Erkata’gir. It was believed that this type of script was not used prior to 11th century. The question over the linear evolution of Armenian script is open for debate, therefore, and it’s only logical to assume that the lack of evidence of the early use of Bolor’gir, Notr’gir and transitional scripts is explained by unforgiving historical circumstances: over 10,000 manuscripts were burned by the Seljuk Turks in 1070 after a 40-year siege of the capital Kapan in the Siunik province of the Armenian Bagratuni Kingdom.

When I began examining the writing systems prior to the creation of the Armenian alphabet, what drew my attention was the ancient Egyptian demotic script because of the close resemblance of some of the characters to Armenian Bolor’gir. I knew that during his research, Mesrob Mashdots had visited Alexandria, Egypt—where demotic script was still in use two centuries prior to his arrival, exclusively for religious texts. The immediate purpose of inventing an alphabet was the translation of the Bible to Armenian. It’s quite logical, then, to assume that Mashdots should have seen examples of demotic writing, but did he make use of them? What is clear is that Mashdots had the intention of orienting Armenians westward, so that the aesthetics of Angular Erkata’gir resemble graceful Greek and Roman inscriptions, and letters are large, erect, and clearly separated. As a script, it’s drawn, not written, and is not suitable for fast correspondence, as it takes a lot of space. It would be very unlikely that a man with such profound knowledge and awareness as Mashdots would limit himself by creating only one type of script, making, may I say, a very unpractical decision.

Armenian letters reveal a complex system of thought at the time of their creation in the 5th century. Interlinked with mathematics, metaphysics, and philosophy, our alphabet remains an enigma. Many questions remain unanswered, but by drawing attention to these historical puzzles we may create the conditions for further investigation and analysis of our profound cultural heritage.

Metaphysics and philosophy of letter form

When we consider the letters, we find their patterns in our memory. We visualize their style. It ‘s much like a musical melody, which naturally and simply finds an emotional response in us, where all elements play a role: rhythm, composition, balance, etc. A hand-written sheet has individuality and a much greater energetic charge than a printed one. Beautiful writing always means illustrative and individual expressions of thoughts, emotions, feelings, and aesthetic views. To some extent, logic is an art devastator and where logic begins, art comes to an end. Art and calligraphy, in particular, a category of metaphysical feature, and detailed explanation prevent us from understanding the essence of a question. It’s possible that only retrospective analysis of calligraphy can comply with logic.

Technique

The art of calligraphy should be as pure and error-free as the performing of musical art, in which an error cannot be corrected because it has already occurred; the only way to prevent it is to perfect error-free master work based on constant training and experience.

The beauty of this craft is in the composition of the buildup, different repetitions, layers, rhythmic intertwining, interactions of large and small scales of forms, use of surface finish, the nature of tempo, speed and movements of the form, and continuity of author improvisation. It fosters a sense of lines, forms, texture, space, and rhythm. On the other hand, it demands a considerable amount of inner effort. But the results—the cultivation of such qualities as diligence, preciseness, patience, attention, and moderation—are irreplaceable. Regular classes with a calligraphic pen and brush help to cope with laziness and to develop a quick eye, the ability to concentrate and think logically. And this, in turn, contributes greatly to the development of artistic thinking and imagination. One of the most important areas in calligraphy is the crispness of stroke endings. When there is doubt in one’s mind, the brush strokes look dull. During calligraphy practice, one should be so concentrated on each stroke that all thoughts on work disappear from the mind, helping achieve a healthy state of spirit. The action of drawing a brush stroke demands confidence. When any other thoughts occupy one’s mind, a perfect line is unattainable.

Calligraphy is the womb of letters, their place of origin, the place where new characters develop. Striving for emotional and graphic expressiveness of a sign was typical of the ancient writing tradition.

Importance of writing tradition in post-modern age

The ancients recognized the importance of calligraphy in forming and developing the human personality. A letter and a word are closely connected with each other, and every letter is significant—the melody of a line, strength of pen pressure, length of a stroke. Writing and lettering stimulate the perception of graphical composition.

Absorbed by scientific and technical achievements of the computer age, we have somehow lost and forgotten something substantial, which is inherent to all of us and played a major part in our evolution—the graphic form of language. The debate over what came first—a verbal word or a graphic sign—is still not over. This phenomenon has always been of a dual nature: What speech is, writing is, and vice versa. For example, when school subjects such as rhetoric were eliminated from the curriculum, calligraphy disappeared soon after. Gradually, then, the meaning of the word and the thought were devalued.

The appearance of a ballpoint pen in 1968 killed the rest of the lettering culture, and led modern society to total dysgraphia (a deficiency in the ability to write). Today children write anyhow, holding pens as they want. As a result, they have poor word stock, and find it difficult to properly express thoughts and ideas both in oral and written forms. The ballpoint pen not only hinders hand muscle movements but also slows down the process of thinking and imagination. No wonder that from year to year, the level of background of undergraduate students deteriorates. It is getting more and more difficult to find such students who are really capable of creative work.

Physiologists and teachers of the 19th century noticed that calligraphy positively influenced the sensory organs of a person, and developed and strengthened his/her character. They believed that “Calligraphy is a medicine and training for human brains and soul.” Long-term research on and the development of methods to prepare specialists have shown that calligraphy is the most effective way to reach these goals, as it broadens the wide range of psychophysical peculiarities of a student. In fact, overtly or covertly calligraphy interacts with other disciplines during the educational period.

Conclusion

I believe that we must use all available means to revive our calligraphic tradition. With abundance of talent but no cultivation or tradition, our children will never fully realize their artistic potential. Primitivism and functionalism emasculated the culture of communication, denying graphic writing the opportunity to improve artistically, and a person to improve spiritually, by the simplest means—using paper, ink, and a fountain pen or a brush. The art of beautiful writing is the link to our past, and given the attention it deserves, it can help to shape our future as the nation of a rich and artistic heritage.

thanks for the inspirational piece. Looking forward to reading your book…

I agree. The piece was inspiring and I also look forward to reading your book.

we can make anything out of the armenian alphabet

check out our new product

http://www.ebay.ca/itm/Armenian-Art-/280783763133?pt=Art_Sculpture&hash=item41600436bd

Hello

I have a number of unique calligraphy art works

If you see fit, you can use the works of Iranian calligraphy artists in your art magazines, either in printed magazines or online magazines.

To introduce the art of Iranian calligraphy art.

Thanks