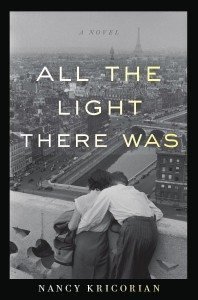

All The Light There Was

By Nancy Kricorian

Boston & New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt (2013)

279 pages, $24.00

Anarchists, communists, liberals, Jews, émigrés—Frenchmen from all walks of life resisted the Nazi occupation in France and the Vichy regime during World War II. They collectively made up what is referred to as the French Resistance. Armenians also joined the struggle, in defense of the France they had come to love. History often belongs to the boldest, the “great men”—and a handful of women—who defined their time. From the ranks of the Armenian fighters, a few names stand out, chief among them the poet Missak Manouchian, a Communist who commanded the Manouchian Group. But there were others whose stories, acts of heroism, and contributions to the Resistance went by unnoticed. Nancy Kricorian’s recent novel, All The Light There Was, peers into the everyday struggle on the domestic front, and offers an unlikely heroine—an Armenian girl who comes of age during the Nazi occupation of France.

Kricorian paints a palpable reality, ushering in the tribulations, uncertainties, and fears that her characters had to face. The story unfolds from the perspective of the 14-year-old Maral Pegorian. Time passes through a different stream—often in fragments marked by different pronunciations of love—for the pubescent Maral. For instance, when she meets Andon, a suitor, time seems to pass in weekly increments as she sees him only on Sundays. “This is the story of how we lived the war, and how I found my husband,” offers Maral early in the book. It is also about the smaller ways in which war affects those condemned to live it (like the meals made of bulgur and turnips), the sacrifices, and the bonds and love that nudge survivors on.

Through her narrator, Kricorian offers us a commentary on women’s roles, and on the demands and expectations an Armenian girl grapples with. Had the story been narrated by Maral’s “mule-headed” brother Missak or his friend Zaven—both aiding the resistance—a decidedly revolutionary narrative would have emerged. Had it been written by Maral’s father, a shoe-cobbler with an affinity for lengthy political discussions, or her mother Azniv, the story may have turned to the politics and events of the time, or about motherly love and grief. But with Maral, the story is told from the physical confines of a young woman living under her parents’ roof. Her home, school, friends’ homes, the Armenian Cathedral, and the parks near her house outline the boundaries of her physical world. Envious of her brother and his friends who are allowed to flirt with fate, Maral often finds herself rebelling against the gender mold she is stuffed into, and being treated “like a hen in a coop.”

Even though the predominant setting is the household—replete with activities such as knitting, cooking, and washing—Maral attempts to burst out of that narrow world. At times she succeeds, running through the streets of Paris as authorities crack down on marchers. Other times, her escape is through her brother and his stories.

Hers is a story of resilience, emotional and physical. Maral is also a “hero”—allowing compassion to lead her actions—as she takes the initiative to save the life of her Jewish neighbors’ three-year-old daughter, Claire. The fate the Jews seemed to face reminded the older Armenians of the horrors they experienced only two decades before. “The child is an orphan. The same as we were. Except we saw it all. Our parents dead before our eyes. Bodies in the dirt. Children with big bellies and heads, arms and legs skinny like spiders. It is the same thing again, Azniv, the way they sent us to die in the desert,” says Aunt Shakeh to her sister, Azniv, in a rare reference to the genocide.

The narrative of the past—the deportations, killings, separations, orphanages—dictates how Armenians see and respond to the events unfolding around them. However, Maral observes that the topic of Armenian Genocide rarely surfaces in conversation. She explains: “It was strange that I knew so little about what they had gone through, especially as it seemed to loom like a vast, amorphous shadow over our lives. My mother and my aunt referred vaguely and ominously to what they called the Massacres or the Deportations. If I asked a question about that period in the Old Country, my mother would say darkly, ‘It’s better not to talk about those times.’ Auntie Shakeh would go pale and invoke God. So after a while, I stopped asking, and it was all I could do to keep from rolling my eyes when they made their dire, cryptic references.”

All The Light There Was is a powerful story of how ethnic bonds can blur allegiances. We encounter Armenians among Nazi collaborators, Allied soldiers, and resistance fighters. We meet Andon the collaborator, whose family hailed from Moush. Andon joined the Wehrmacht after he was recruited from a German camp, where he was being held as a Soviet prisoner of war. We meet Zeitountsi Hrant, the American soldier from New York. And there are the Armenian Resistance fighters like the Kacherian brothers, Zaven and Barkev.

They all have a bond that connects them: They are the children of genocide survivors dispersed across the globe. And so, the Armenian identity comes first before the other, hyphenated identity. In one revealing moment, Maral’s friend Jacqueline, upon meeting Andon, says, “I know that under that German uniform, there beats an Armenian heart.” Maral is at the intersection of all these identities, and it appears she is tasked with reaffirming these bonds, sometimes with as little as a symbolic kiss.

War emerges as a miasma of dead romances, dead boys, POWs, food shortages, tuberculosis, hunger, betrayal, and the hellholes they called work camps. Following news of the death of a loved one, Maral sees her loss and pain not as uniquely hers but as an affliction that indiscriminately targets victims everywhere: “I didn’t know what to feel or think. I observed the three of us from above, small people in a small apartment, bent with grief. This scene was playing itself out in apartments and houses all across the city, all across the continent, and all around the world. The war was a great factory of suffering, all of it fashioned by human hands.” All the Light There Was is a story of loss, love, and finding the guiding light when darkness prevails. As Maral’s father says, “This world is made of dark and light, my girl, and in the darkest times you have to believe the sun will come again, even if you yourself don’t live to see it.”

To watch CivilNet’s recent interview with Nancy Kricorian, click here.

Nicely written

article on On all the light there was

Often used that dark and light similiar reference to all those students I have helped direct as a hs teacher ,adjunct professor and Div I college hockey coach Mike Geragosian

I read the book a few weeks ago. I highly recommend it.

Thanks for this beautifully written and insightful piece. As a writer, the only thing more gratifying than a reader who fully understands the project one has set out for oneself is when that reader writes a review. I am honored.