During the Soviet era in Armenia, there were virtually no non-governmental organizations (NGOs). After the devastating earthquake of December 1988 and during the years of the war in Artsakh (Karabagh), NGOs began to form and were heavily involved with relief and humanitarian efforts. The government of Armenia was unable to cope with the dire situation resulting from the earthquake and the war, and therefore had to accept the active participation of civil society organizations (CSOs).

Alongside humanitarian aid, major international organizations and NGOs started contributing to the development of the local non-government sector. Major Armenian organizations from the diaspora also provided humanitarian aid and contributed greatly to the reconstruction process.

The focus of these new NGOs was on refugees, women, children, the elderly, and the disabled, but their activities were somewhat limited. Their inability to meet the growing demand for emergency services and operations, for example, was due to a lack of local NGO skills, knowledge, and capabilities, and the absence of an appropriate legal framework. This period can be considered the first stage in the formation of local NGOs.

Even though most of the NGOs were located in Yerevan, local NGOs began emerging in the marzes (provinces), too, and implementing projects in education, health, culture, community development, and income generation. In 1997, the number of local NGOs passed 500. By 2001, data from the state register showed that 2,585 NGOs were officially registered. In 2010, the state register reported 45 international NGOs and 5,700 local NGOs. However, out of the total number of local NGOs registered, only 15 percent can be considered operational; most in that percentage are small outfits that are not active, and some have vague and obscure missions. The following are the mission statements of a few such NGOs:

–The main goal of the organization is to participate actively in the social and legal life of the country in order to promote a free and safe life for the youth.

–The main goals of the organization are to develop art and psychology and to form civil society.

–To organize and collect all the recipes of Armenian national cuisine and publish it. To participate in international contests, seminars, and meetings.

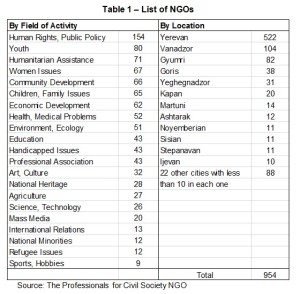

Table 1 presents a list of operational NGOs and their fields of activities, although not all are necessarily active.

International NGOs can be classified under the same categories as local NGOs, but have two additional categories—(1) infrastructure development and construction, and (2) capacity building and technical assistance for local CSOs, self-governing bodies, and community councils.

A survey conducted by World Learning revealed that in the 1990’s, 70 percent of NGO leaders were women. However, by 2001, 58 percent of NGO leaders were men, and by 2009, the percentage of male NGO leaders had increased to 63. The shift might have occurred as men came to view NGOs as a job opportunity and a means to further their careers.

Yet, while in 2004, approximately 75 international NGOs were operating in Armenia, that number has since decreased. The reason for this decline may be the stable economic growth seen in Armenia in 2006 and 2007.

Government involvement

The gradual increase in the number of international NGOs in Armenia and the corresponding need to regulate the activities of all types of CSOs led to the Armenian government adopting its first Law on Civil Society Organizations in 1996. The law encouraged international NGOs to shift their activities from emergency response to development, the protection of human rights, and enhancing the capacity of local NGOs. The law states that Armenia recognizes the crucial role of NGOs in the development of civil society and aims to promote the establishment of NGOs as legal entities. The government has also passed decrees, regulations, memorandums, and agreements related to cooperation with NGOs, and formed institutional bodies and units on community and national levels.

Voluntarism

When interacting with society, NGOs in Armenia, in comparison to NGOs in the Armenian Diaspora, use an informal and less structured process for volunteering. NGOs in Armenia also have greater issues with volunteer mismanagement; sporadic volunteer recruitment; lack of skills assessment, orientation, and training for volunteers; and recognizing volunteer contributions. Engaging volunteers in long-term regular commitments, instead of ad hoc projects, could better utilize this important resource.

Because voluntarism for society was not a common practice during the Soviet era, there is a need to widely publicize the value of volunteerism to get more people interested. Presently this important human resource is underutilized by NGOs in Armenia. NGOs should realize the expectations of the volunteer in order to retain their involvement and commitment over time. A non-profit organization with a strong and committed volunteer base is also more likely to attract new funds.

Democratic governance

The internal democratic governance of NGOs in Armenia is another issue that needs to be addressed. NGOs have developed written policies for democratic governance, but often do not follow these policies. They hold elections to select their internal leadership, yet the rotation rate of such leadership is low. Typically, the founders of NGOs hold their positions for a long time, which affects the formation of an independent Board of Directors.

While most Armenian NGOs have bylaws and constitutions that outline their governance mechanisms, it sometimes seems as though these mechanisms are developed only to get the required permits and to attract new funds, rather than from a genuine interest in democratic management. Members are also often excluded from decision-making processes. Unless NGOs embrace democratic procedures into their regular operations, they will not be able to establish a credible reputation in the community.

Funding sources

Financial sustainability is one of the main challenges that local NGOs in Armenia face. It is this challenge that limits their capacity for impact and distorts the image of civil society as a financially dependent sector. It is necessary to diversify funding sources by fostering partnerships with a full variety of potential funders, whether they are individuals, corporations, or governments. NGOs in Armenia undertake fundraising activities through various events, exhibitions, concerts, and other activities. However, the majority of NGOs have difficulty with fundraising because they lack experience in fundraising methods, basic marketing, and financial management skills.

The activities of Armenian NGOs are heavily reliant on external funding. Some donor organizations work directly with NGOs, while others operate on a bilateral or multilateral basis. The Armenian Diaspora also assists the local NGO sector by allocating funds or providing in-kind assistance. Many NGOs believe that if donor organizations leave Armenia, the scope of their activities will be curtailed and they will become non-operational due to a lack of funding.

The Civil Society Fund is one of several programs supported by the World Bank, which has provided grants since 1999 to NGOs and other CSOs in Armenia. The grants support activities related to civic engagement, and focuses on empowering people who have been excluded from society’s decision-making processes. The individual grants are between $8,000 and $10,000.

Today’s unfavorable legislative framework related to donations to non-profit organizations does not provide the NGO sector with an opportunity to acquire alternative financing. Therefore, limited and unsustainable funding from donors and the government make the NGO sector more dependent, which in turns affects their independence and sustainability. Furthermore, the Armenian business sector does not invest in NGO development. (If it does, the investment is limited to a one-time project or event-based charitable contributions.) Often NGOs are forced to accept funding for projects that are not in line with their mission, values, or principles; the project requirements are often determined by the donor’s agenda, and this greatly affects credibility of the organization. Armenia’s state budget allocates some funds for NGOs on a competitive basis.

Lack of transparency and accountability is another issue facing NGOs, which generally do not produce and disseminate annual reports and financial statements. The majority of NGOs claim that their financial information is publicly available; yet, on closer inspection, it becomes clear that they rarely report to their beneficiaries when it comes to the finances and the quality of their work. The majority of Armenian NGOs think that the preparation of reports requires additional financial expenditure. Reporting of finances and activities would improve the public’s perception of NGOs.

Effectiveness

One of the underlying causes of civil society’s weak effect on policy and social issues is that NGOs have failed to extend their outreach and rally greater support and higher levels of citizen participation in their activities.

Long-term financial insecurity stands as another hindrance to the number of CSO’s in Armenia. NGOs have relied solely or predominantly on international donor funding, without diversifying their income sources or developing a long-term strategy to change this situation. As a result, the instability of work in the NGO sector has not attracted young specialists.

Increasing the professional skills of CSOs through trainings and staff development could help strengthen the level of organizational development and achievement. What is critical is focusing on staff retention, as well as establishing a culture of information sharing and knowledge transfer.

Fragmentation and competition among NGOs occur frequently, resulting in an ineffective system for Armenian CSOs. Because of limited coordination among NGOs, the sector lacks updated information and a database of NGOs. This creates an inadequate picture of these organizations and, consequently, gives people a poor perception of NGOs. This also affects the ability of NGOs to influence the decision-making process in the public sphere.

Some issues facing civil society include a short-term approach, lack of strategic thinking, clustering around pro-government or opposition groups, and poor organizational capacity. In order to increase citizen participation and sponsorship, NGOs must realize that they should be deriving their legitimacy from society, as they depend on popular support. Increased transparency and accountability are vital to support this action. This includes reporting to beneficiaries just as they do to funders, and presenting an inclusive account of all aspects of their activities. Improvements in these fields will contribute to increased levels of trust with the civil society sector and the broader society, and will foster increased citizen participation.

Sources

Civil Society Briefs, Asian Development Bank, Armenia Resident Mission, November 2011.

Armenian Civil Society: From Transition to Consolidation, CIVICUS, Civil Society Index Policy Action Brief, 2010.

The Professionals for Civil Society NGO, database of NGOs, World Learning, Inc.

Great commentary and a very well-rounded review of the status of these efforts in Armenia. Thank You.

Armenia’s Western funded NGOs are a serious threat to the county’s normal development and should thus be shutdown.

. . . And only non-Western-funded NGOs should be allowed. . . God bless the “rise of Russia.”

All nation states are works in progress… as are their citizens’ perspectives and levels of experience with democratic process. Tensions between resident and diaspora actors are to be expected although the friction between the two can be as productive as it is painful…. the challenge is for both sets of actors to stay in the game for the long term.

Just by reading the first sentence I could understand that the author has no idea what he’s talking about. Or he does, but wants the unsuspecting readers to get confused even more about “The big old ugly Soviet Times”… So, why would somebody lie that “During the Soviet era in Armenia, there were virtually no non-governmental organizations (NGOs)”?

No Western funded grant processing machines that’s for sure. What else he could be talking about mixing together NGOs, CSOs, non-profits, charities, labor unions, professional societies – all conveniently labeled “non-governmental organizations” by US government bureaucrats from the US Agency for International Development? If they are funded by a foreign government, they become quasi-governmental organizations. The only difference is that it’s not the Armenian government, but foreign governments who control them.

Dear Colleagues of CSOs in Armenia,

Greetings from Save the Earth Cambodia.

I am writing to connect with the agencies those are experienced to work in the Solid Waste Management.

So, please help me to connect with the CSOs that are working/experienced in the Solid Solid Waste Management.

You kind assistance to connect me with the respective CSOs is highly appreciated

Hello,

we are a NGO from western Poland.

http://www.naszpomost.pl

We wolud like to develop some projects with Armenian partner, for example in the field of education , scoial exclusion, democracy , the youth development and so on.

Would be nice you to pass my email to somebody.